History - Rev. Haddock Murder

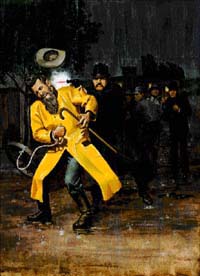

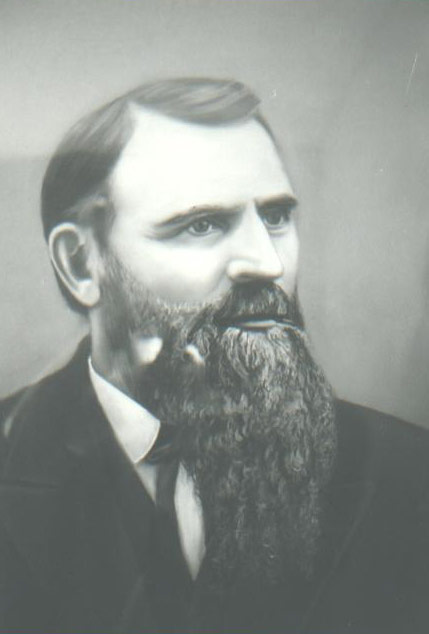

Click on The Martyrs Plaque (to the left) to see pictures and items that share with you more about Rev. Haddock and the church he served here in Sioux City. Items include the original Martyrs Plaque as well as a painting of Rev. Haddock, pictures of the church he served and pictures excerpted from the book "Hero and Martyr: The Life of George C. Haddock".

Click on The Martyrs Plaque (to the left) to see pictures and items that share with you more about Rev. Haddock and the church he served here in Sioux City. Items include the original Martyrs Plaque as well as a painting of Rev. Haddock, pictures of the church he served and pictures excerpted from the book "Hero and Martyr: The Life of George C. Haddock".

The murder in 1886 of Rev. George Haddock, Pastor of First Methodist Church and an outspoken critic of liquor sales in Sioux City, prompted city to clean up its act.

By Russ Gifford, (Reprinted from "The Weekender")

07/29/04

|

|

courtesy of the Pearl Street Research Center

Not far from Prospect Hill, at the intersection of Fourth and Water streets, George Haddock was working to rid the area of prostitution, saloons and crime.

|

On Aug. 3, 1886, when the Rev. George C. Haddock crossed the muddy corner of Fourth and Water streets, a shot rang out that would forever vault him into the Iowa history books.

As an outspoken critic of liquor sales in Sioux City, his efforts were paying off - saloons closed, and word by his Methodist parishioners spread about the need to end the flow of the drink he so despised. Change was surely on the horizon, Haddock surmised. But Haddock was about to pay for his efforts, and it was a steep price.

But would it be worth the cost?

That and other ideas will be the topic of a Sioux City Museum discussion at their Aug. 3, "Twilight Talk" which will explore the history of liquor and prohibition in Iowa.

Raucous nature

Sioux City's raucous nature was a part of her heritage. If rivers were the 19th century's roads, the Missouri was a superhighway. Steamboats carried prospectors and speculators to the open frontier of Montana and the Dakotas, looking for fast fortunes and easy rewards. Sioux City served the needs of the numerous travelers that passed through the town, supplying mining equipment, clothing, and of course, food, entertainment and plenty of drink.

And drink they did. By 1886, there were 75 saloons to cater to the travelers and the locals, supplied by two breweries. With the liquor also came gambling and prostitution, and Sioux City met these needs as well. In places like Hell's Half Acre, conveniently located at the base of Prospect Hill (near Wesley Way near the Veteran's Memorial Bridge), easy virtue and violence were as prevalent as the liquor, according to reports.

In July of 1884, two violent deaths occurred in Sioux City, fueled by drink and gambling. Many saw banning liquor as the only way to curb the violence.

The fight to ban liquor sales in the state and the nation - the temperance movement, as it was called - had been led by the Protestant churches. Their preachers fulminated from the pulpit about the sins of free flowing liquor and the less than virtuous life it created, and the Republican Party took up the cause as they had the fight for abolition of slavery a generation before.

In Iowa, in 1882, these groups prevailed in the Legislature and a Republican governor signed the liquor ban into law. But Sioux City saloons flaunted the law and continued to provide their customers with drinks.

Illegal operators

As a frontier town, the city fathers tended to identify more with the open territories than with the laws of the rest of the state. And so, the Clark Law - as the anti-liquor law was known - was ignored in favor of a continuation of a municipal licensing agreement - clearly illegal, but clearly profitable. The saloons would continue to operate, at least until someone forced the Sioux City Police to accept the state law.

|

|

Haddock

|

The 'Fighting Preacher'

As before, the churches were the only ones organized and willing to make it a fight. Rev. Haddock of Wisconsin knew a thing about fighting. He'd grappled with the drinking problem in Wisconsin, and saw Sioux City as the extension of the same battle.

Haddock, a big man, was not intimidated by the threats. Known as the "fighting preacher," it was rumored that it was more than a nickname. In the next year, he and other ministers made surprise visits to saloons, and then testified against them in the courts, to push the police to close the saloons.

By 1886, he was succeeding. To his parishioners, he was a hero. To the saloon owners, he was an irritant, and a growing threat, and they decided it was time to tame him.

On Aug. 3, Haddock had spent the day in court, testifying against a saloon. Afterward, he and another minister rented a buggy to visit Greenville, about 2 miles west of Sioux City, to see if they were violating the state liquor law. The trip was a bust - the saloon was closed, and they found nothing.

Upon his return to the Jerry Merrill Livery stable at the corner of Third and Water streets, a group of men awaited him. Haddock stepped into the muddy street, and walked toward the men. It was 10:15 p.m, and he was armed with nothing more than his convictions and a small metal pulley wheel on the end of a rope.

Later testimony would say two men from the crowd approached Haddock before he crossed the street. The first man hid his face behind his hands, and as the two passed Haddock, the other turned and shot Haddock from behind, striking him in the neck. Knocked to the ground by the shot, the valiant preacher struggled back to his feet, then tried to reach the curb, and fell again. Haddock bled to death near the sidewalk (at the corner of Fourth and Water), his blood staining his coat and the street below him.

Conflicting testimony

The police quickly tracked down the man witnesses named as the killer - John Arensdorf, the foreman of a local brewing company. But his trial quickly degenerated into a morass of conflicting testimony with the defense contesting everything. It ended in a hung jury when 11 jurors voted for acquittal, with one valiantly holding out for the conviction. As the Chicago News wrote at the time, "Even should the spirit of Dr. Haddock himself enter the room and point to Arensdorf and say 'Thou art the man,' the jury would still not convict the accused."

It was no great surprise when a second trial found Arensdorf not guilty. Later, another man was sentenced for ordering the death, but he didn't serve long before the new governor - a Democrat who opposed the Clark Law - commuted the verdict.

At Fourth and Water streets, a small marker commemorates Haddock's sacrifice. Did he die in vain? No. Haddock's murder and the transparent corruption of the trial made headlines nationwide. Many held the community up as an example of sin and evil in the world. In their embarrassment, Sioux Citians recognized the need to clean up their town. The City promptly threw out the saloons, gambling establishments, and the prostitution houses, most of which took a ferry across the river to create Covington, later known as South Sioux City, Neb.

At Fourth and Water streets, a small marker commemorates Haddock's sacrifice. Did he die in vain? No. Haddock's murder and the transparent corruption of the trial made headlines nationwide. Many held the community up as an example of sin and evil in the world. In their embarrassment, Sioux Citians recognized the need to clean up their town. The City promptly threw out the saloons, gambling establishments, and the prostitution houses, most of which took a ferry across the river to create Covington, later known as South Sioux City, Neb.

But Sioux City turned a corner toward the future with Haddock's death. Though Clark's Law was repealed within five years - and liquor problems would be the root of later police corruption scandals - the first steps toward making Sioux City less of a lawless frontier town had been taken.